Talking Accountability, Trauma, & Healing with Network for Victim Recovery of DC

Since 2012, Network for Victim Recovery of DC (NVRDC) has been empowering survivors of all crimes by offering them a continuum of advocacy, case management, and legal services. Their work is community-driven and guided by the belief that survivors deserve respect for their dignity in the aftermath of a crime. Recently, they launched the TraumaTies podcast and the Trauma-Informed Education Project — two of their latest efforts to educate the community about survivor-defined justice, and about the underlying and systemic ties between trauma and our daily personal experiences.

On the heels of their podcast’s season finale, the Catalogue for Philanthropy had a chance to speak with their Executive Director Bridgette Stumpf and their Head of Services Lindsey Silverberg about their experience creating TraumaTies, how they approach their work at NVRDC, and more.

Catalogue: How would you describe survivor-defined justice?

Bridgette: Survivor-defined justice is the core concept that someone who experiences harm from violence knows and understands their lived experiences, their needs, and what will make them feel safest moving forward better than anyone. Regardless of our experience and expertise, we trust and recognize that the person we’re trying to support is the expert of their own lives, instead of us being the ones defining what will move them through the process of healing.

We also know that survivor-defined justice recognizes that the traditional sense of justice — the criminal legal system — has not brought healing or equitable healing to survivors of violence, so it creates this understanding that the traditional notion of justice may not be safe for everyone.

Catalogue: What are some of the barriers preventing survivors from achieving survivor-defined justice, and how is NVRDC changing them?

Lindsey: There are lots of things that prevent survivors from achieving survivor-defined justice. Some of it is what society tells crime survivors they’re “supposed to do” after experiencing violence and harm. Some of it is systems in this country being racist and sexist. (Instead of valuing) survivors’ or victims’ involvement in the outcome when harm is caused, it’s much more about focusing on — in my opinion — retribution for the folks who have caused harm (rather than) actually healing the people impacted by violence and trying to repair that harm. Broadly, those things impact a person’s ability to achieve survivor-defined justice.

But I (also) do think it’s individual — depending on who the survivor is and if they’ve interacted with those systems before, they may not trust (the systems) or believe in engaging with them. And because we don’t have a system that really values their experience and puts them at the center, some people don’t even view it as an option.

The other hard thing with survivor-defined justice is that (society) only values certain survivors, whether that be based on race, age, socioeconomic status, or the type of violence someone experiences. As a society, we look at things like power-based violence with much more importance than someone who experiences community violence, and all of these things are very tied together.

Some of the ways NVRDC is trying to transform the system is by creating alternatives outside of the criminal legal system like restorative justice. We strongly believe that restorative justice and transformative justice are real options for folks who want to engage and have conversations around accountability and recovery. We want those to be widely available to all survivors.

Bridgette: One of the ways we specifically thought about barriers is applying survivor-defined justice that focuses on the intersection of racial equity and victimization. We have a partnership with the (Community Violence Intervention program at Medstar Hospital). a lot of the data shows that when we intervene with someone who’s experienced community violence at the hospital, we can not only give that person healing and the opportunity to not have retaliatory violence, potentially, but we can also move towards real and community healing.

One of the things we’ve done is place a crime victims’ rights lawyer at the heart of how that patient comes in (to the trauma bay) with a life-threatening injury, so that they can access supportive services and learn about their rights. Treating them as a crime victim has historically not been the case — the vast majority of people presenting with gunshot wounds to the trauma bay are young men of color. There is often an assumption by law enforcement or others who are involved in a potential investigation and treatment of that individual that they somehow did something to cause what happened to them, and that’s deeply rooted in racism and other oppressive ideas and beliefs. But giving that individual access to the same crime victims’ rights that a sexual assault survivor would get walking into the same emergency room is really a concrete way that we’re trying to infuse equity into healing, so that someone based on their identity is not experiencing different options and resources as a crime victim simply because of that identity.

Catalogue: How have you seen the conversation around trauma shift since COVID and what are some changes you feel more positively or more cautious about?

Lindsey: From the standpoint of people knowing that trauma is a real thing folks experience, that’s a positive cultural shift we’ve seen since COVID. I see a lot more people out there with social media content talking about the collective experience we’re going through, (which) is a trauma for a lot of individuals. The places we’re hoping to create and see change are in these broader sectors, so that folks recognize that when they interact with someone who’s having a reaction that they don’t understand, or that doesn’t feel balanced with what’s going on in the situation, it might be due to a trauma. We want people to know that you’re going to intersect with and potentially impact how somebody is experiencing trauma in all sorts of sectors. There’s a lot more as a community, in general, we could do to help support folks experiencing trauma.

Bridgette: Trauma is both common and unique. As we normalize it and start to recognize it as a common experience, we fail to see that it’s also a unique experience. People often expect others to respond in the same way we did. We don’t have the education or awareness to know that people might be very different. Often, without further and deeper understanding of the uniqueness of trauma, we unfortunately can go to a bad place — we will question the validity of someone’s trauma experience when it doesn’t mirror ours. That’s the danger of commonality.

The second danger is we can become desensitized. If people think trauma is just a buzzword, then we don’t take it seriously.

There’s a distinction in healing from trauma when it’s a shared community trauma versus an individual trauma. For me, the value of COVID is we now all know what it feels like. We were connected. And that’s why shared healing is a little bit easier because we feel understood. But when we talk about unique traumas like sexual violence, those can be more isolating. When we only know about trauma through a shared community trauma experience, we may not understand the framework of unique individualized trauma where you’re not able to seek help or where you don’t feel believed. And I think that disconnect can almost widen the current gap in shared language that we now have with trauma, even though we might be better at understanding what our own experience was.

Catalogue: What were some of the challenges with creating TraumaTies and the Trauma-Informed Education Project?

Lindsey: It’s a very niche topic. It’s also a very hard topic, and one of the reasons people often don’t like talking about or acknowledging trauma is — at least in the U.S. — we don’t talk about shared hardship. We like to create distance. So, for people to be engaged or want to learn more, there’s vulnerability there. We’re asking them to come along on this journey with us (when) it might be hard to listen to or hear about.

Bridgette: For me, there’s this sort of initial barrier. We love the name TraumaTies because it really captures the spirit of what we’re trying to do, that we’re all connected, but it just won’t be for (some people). So, how do we connect people who don’t know or who don’t want to know? We’ve created a culture where it’s shameful to be vulnerable and authentic, and that’s because we’ve attached weakness to this concept of trauma that’s absolutely not true. We talk about (trauma) being our bravest moments as a human species — not only do we keep ourselves alive, but our brains are (also) smart enough to know and predict places where we might be in danger again.

Another thing that has been challenging is the timing of how the podcast works. We often talk about mass violence because Lindsey’s time responds to mass violence, but it’s one of the key examples where we think about trauma in our youth and how conditioned they are to doing school shooting drills. We talked about that and then the Uvalde shooting happened. How do we give folks a warning that we’re having these conversations when they may have been directly impacted by something that we didn’t even know about? So, being trauma-informed in the actual production of the podcast was a challenge and something that we have to continue thinking about.

Catalogue: How have things changed since NVRDC was founded?

Bridgette: For me, (it’s) the intentionality about how we approach the work and clearly identifying the direction of the problem we’re trying to solve. Our Theory of Change was a four-year-long process of using our staff, stakeholders, and board to look at all our different services and the scope of our services, and think about what we’re actually trying to fix. We know the existing response to harm from violence is not adequate to create true healing in our community, particularly not for those who are marginalized. How do we solve that really big problem? We’re not going to stop crime, but how do we create a dignified and empowering experience any time someone experiences violence from crime?

We crafted that into three intentional pathways of where we do our work. Empowerment includes a lot of direct services — legal support, crisis response, advocacy. We also have transforming systems, so restorative justice and building out these partnerships. In addition, we really want to talk about culture shifting, so actually changing (people’s) hearts and minds and attitudes and beliefs. How can we change the way anyone and any sector shows up when they’re interacting with someone who has a trauma history? That thought process and approach was the impetus for our TraumaTies podcast and Trauma-Informed Education Project.

Lindsey: The way I’ve seen us transform is really from being actors within the system to recognizing and building the power and places at the table where we feel like, now, we can shift that. That’s been the most exciting and the most impactful, besides our day-to-day work with survivors.

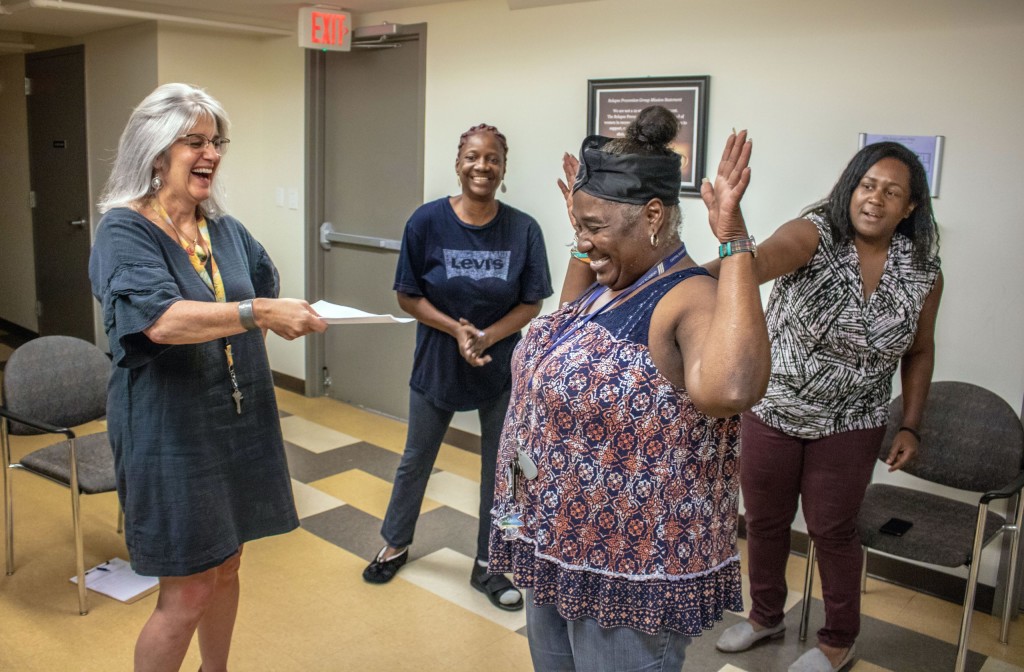

Bridgette: Thanks to Lindsey’s leadership and the leaders who have stepped in under Lindsey, we’ve (also) changed a lot internally and that shows up in our Theory of Change as well. We’re really being aligned in how we live those values beyond the words on the paper. I’m intentional with naming that I’m a white leader and that we serve a lot of women of color. We publish the demographics of our staff and board on our website and we try to be transparent with the community who seek our services, so they know who they’re going to interface with. We recently had a staff member (on the second podcast episode) build out an entire therapeutic program grounded in cultural responsiveness for Black women seeking therapeutic services. We’re really thinking about how we can (embody) those core values, not just with our external stakeholders, but internally with our staff so we can sustain the passion of the folks doing the work that makes survivors’ experience better and strengthens the sustainability of the whole organization.

Catalogue: Where do you find hope in your work, and what’s coming next for NVRDC?

Bridgette: One thing I’ve found hope in — recently, I went on a trip with my friend (who) has really struggled in her life around shared family experience in a faith community. We were listening to the first episode of TraumaTies and she paused it and said, “I finally realize that was traumatic for me. Having that experience was trauma.” Just seeing that moment when someone accepts that something they’ve carried their entire life, which has been extremely painful and damaging, actually wasn’t them and was this trauma experience was really beautiful.

Lindsey: If we can get that to one person, then for us it’s a success.

I had an elderly dog that I was taking to the vet to get acupuncture, and I was talking to the vet about how much trauma they see. They have one of the highest death-by-suicide rates out of any profession. When we were talking about this, the places where trauma shows up, so many people don’t think about that. We want people to make connections and we want them to feel like their experience matters and they are seen in the ways in which this might impact them.

That’s what we’re going to be doing in season two. We’ll be getting into the unsung heroes of people who are impacted by trauma.

Listen to the TraumaTies podcast and learn more about the Trauma-Informed Education Project. Visit NVRDC’s website to view their other programs and offer your support. You can also stay updated on their work through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and over email.