I’ve always loved movies. I come by it almost genetically. My father taught film production at various universities during my childhood, and I grew up on a steady diet of indie, niche, and foreign films: The Last Unicorn and The Point probably being the two most memorable and most watched in our household.

But it was in Argentina, on an academic research grant, that I fell in love with film. Not “movies,” but film itself as a medium.

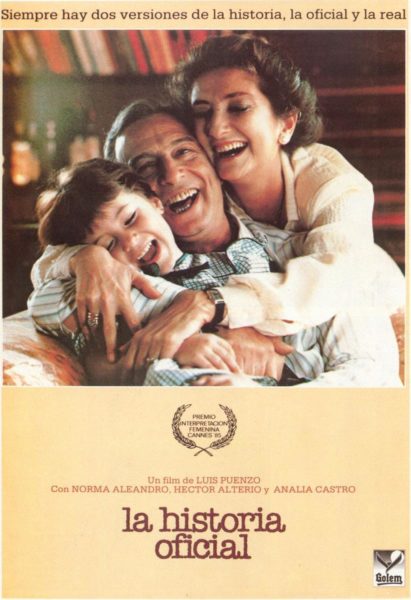

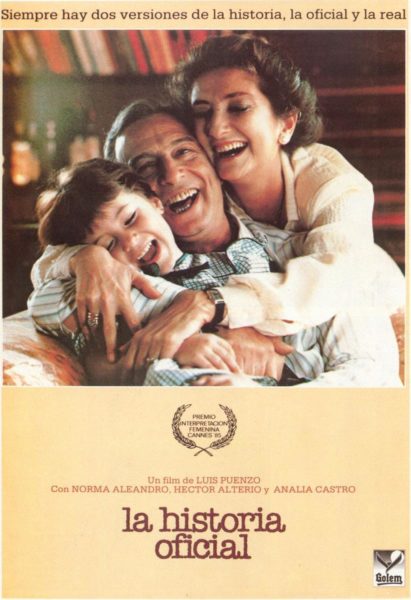

I went to Argentina with a single, albeit complex question: how does a society heal from trauma on a massive scale? Argentina suffered a brutal military dictatorship from 1976 until 1983, during which time over 30,000 “leftist rebels” were “disappeared” by the regime. In 2007, when I was doing my research, the nation was still grappling with the fallout. For a while after my arrival, I posed that single question to everyone I met, and at first the answer surprised me, until I’d gotten the answer so many times it couldn’t be coincidence. Most Argentines I spoke to directed me to a single film: La historia oficial (The Official Story).

La historia oficial tells the story of Alicia, a high school history teacher who is leading a comfortable life with her husband, Roberto, a businessman with ties to the military, and their adopted daughter. When Alicia begins to wonder about the identity of her daughter’s birth parents, she finds herself suspecting that she may be the child of people abducted or killed by the government. She is faced with an impossible choice: live knowing her child is missed by her real family or give up the thing she loves most in the world.

The film came out as Argentines were first learning that, during the dictatorship, children had been abducted from rebel parents and given as rewards to those loyal to the regime. As a country, they were struggling to cope politically and legally with the issue. But the film gave the country a glimpse into the individual, personal heartbreak obscured by the headlines: that real mothers, both biological and adoptive, were being faced with a no-win scenario. And in making the political personal, the film kick-started a national healing process.

What made me fall in love with film was understanding that it is so much more than entertainment or even education. Film is, to my mind, the most visceral way to tell stories, and humans need to tell stories. It’s how we understand ourselves, our families, our communities, and ultimately, our entire society. Stories define our nation, our religious traditions, and even our most intimate unit: the family. Those stories tell us who we are.

While I have been, from my youth, a great believer in the power of film, after my time in Argentina, I see it as a vital necessity to any community.

But film in the U.S. today has a problem. Our media is evermore mediated, and the stories that need to be told aren’t getting out there. Six companies own almost all media: and that’s not just film, that’s news, television, online portals, and more. The barometer they use on funding film projects is what will make the most money, not what stories need to be told. So they put their faith in what they know: the same old directors and regurgitated plotlines. And since the studios hold all the cards, they can charge gigantic licensing fees, ask for 90 or 100% of a theater’s ticket sales, and even take a cut of concessions sales. The only way to survive in that context is to be a giant corporation with pull of your own, and even then to survive, the multiplexes charge prices so high that film is becoming increasingly out of reach for the average American (whose income is decreasing).

That’s why, in 2015, when I met Dr. Caitlin McGrath, I was immediately hooked on her vision to turn the Old Greenbelt Theatre into a nonprofit, arthouse cinema. Revitalize this a historic gem of a theater by: showing films that make people think; creating a space where the community can come together to digest, unpack, and process these films; and do everything possible to make these films accessible to everyone?regardless of age, income, or ability. It’s what every community needs, and we are beyond lucky to have this resource in Prince George’s County.

The Old Greenbelt Theatre is run as a nonprofit because we are mission-driven, not profit-driven. As a nonprofit, we can solicit the support of our community so that when we lose money showing a film (which we regularly do since studios can demand such a deep cut of our profits) we can still exist to screen more films that our community wants or needs to see. If we were worried about a wide profit margin, we wouldn’t have brought you Transit, If Beale Street Could Talk, Boy Erased or even First Man.

Independent movie theaters are closing down all across the country. They can’t compete in a corporate world that is cannibalizing the very locales that show their films. But there are important movies being made that need to be seen and not on a smartphone (as much as I applaud Netflix and Amazon for picking up the mantle of independent filmmaking). Film is at its most powerful when witnessed in community.

That’s what we’re doing here at the Old Greenbelt Theatre. As a nonprofit, we bring you films from screenwriters and directors outside the mainstream. We provide a place to experience these films in community, and I truly do mean experience, because we follow up so many of our screenings with guest speakers and Q&A sessions. It doesn’t pay to do guest speakers. It’s something we do because it’s important.

We’re a nonprofit because we serve a vital role in our community. We aren’t providing bread or shelter, that’s very true. But in many ways, we are creating a safe haven. A place where people of all walks of life can come, see themselves on the big screen, and have their experience understood by the community. We’re helping tell the stories our community needs to hear, and stories are the very stuff of which community is made.

By Kelly McLaughlin, Director of Marketing & Development, Friends of Greenbelt Theatre